Advertisement

Outside-The-Box-Learn-From-The Master

I’m a dedicated wildlife artist, painting mostly North American birds and mammals, because I’m fascinated with these creatures. Great subjects can be found almost anywhere, and they’re just waiting to be painted a sparrow sitting on a window ledge, a turtle sunning on a log or a quail running in the brush. But despite the recurrence of my subjects, I make my paintings stand out from the others in my genre (and I never get bored with them) because I allow myself to go beyond the usual painting formats and explore new areas of the picture.

I’m a dedicated wildlife artist, painting mostly North American birds and mammals, because I’m fascinated with these creatures. Great subjects can be found almost anywhere, and they’re just waiting to be painted a sparrow sitting on a window ledge, a turtle sunning on a log or a quail running in the brush. But despite the recurrence of my subjects, I make my paintings stand out from the others in my genre (and I never get bored with them) because I allow myself to go beyond the usual painting formats and explore new areas of the picture.

Giving my wildlife paintings an odd size brings an added vitality to the subjects, and it makes them not only more exciting to paint but more interesting to view as well. It challenges me as an artist to be more creative in relating the background to the center of interest. After all, a painting size of 61/2 x 291/2 would challenge almost anyone’s creativity! I’ll show you how I go through the process of searching for the right format, and then how I paint within these new parameters, and with this I hope you’ll begin to expand your painting horizons, too.

A Different View

From the window of my studio I often see nuthatches (small, tree-climbing birds) moving from limb to limb and clinging to tree trunks-even hanging upside down. The acrobatic subject of A Different View (watercolor 32x11) was perfect for painting in a tall format, and I emphasized this with the strong vertical shapes of the tree trunk and branch. I used the negative space of the background and the delicate texture of the lichen to further accentuate these shapes.

Exploring the Possibilities

Before placing any paint on the paper, I like to take the time to explore some of the different formats that can be used with each subject. Does the center of interest lend itself to a tall vertical painting, a long horizontal one or a traditional square one? For wildlife, the clues to answering this question are usually in the creature’s habitat. A bird may be perched at the end of a long and complex branch, or atop a curiously twisting tree trunk.

A mountain lion may be resting beside a variety of bushes or a stream full of beautiful reflections. Often there are natural lines in the environment that I can use to guide the viewer’s eye toward the painting’s center of interest. Unless the right format comes to me immediately, I’ll make pencil sketches that try out a variety of shapes before I settle on the one I’m going to stick with.

It’s important to remember that a painting’s center of interest doesn’t always have to be slightly off-center in the frame of the picture, where it usually is. Putting it far out at the edge can give the reader a distinctly different visual experience because instead of focusing first on the subject and then absorbing its environment, the viewer most likely sees the environment first, and then moves on to the subject within that established context. Even when the center of interest is near the center of the painting, extending the borders far out into the surrounding area provides a much deeper setting, enriching the sense of place and prolonging, in effect, the viewer’s exploration of the scene.

Laying The Groundwork

I prepare my painting surface by mounting 140- or 300-lb. Arches cold-pressed paper to a heavy, acid-free board using acid-free glue. I prefer making my own watercolor boards because I’ve found that the commercially prepared boards just aren’t tough enough to stand up to all the sanding and scraping I’ll subject them to. When the glue dries, I’ll have a surface that can be totally saturated with water without buckling or warping, making it ideal for working wet-into-wet.

Once the surface is mounted, I draw the scene with a 3H or 4H pencil, but I do it lightly enough to keep from scoring the paper. I’ll provide only as much detail as I need to get an accurate likeness of the major elements, and the background will be loose and sketchy-just enough to give me an idea of where to place the shapes and vary the textures. Essentially this drawing gives me an idea of how I’ll work the painting by allowing me to anticipate the direction of my brushstrokes and to visualize the relationships of light to dark, negative to positive and texture to shapes.

Painting Away

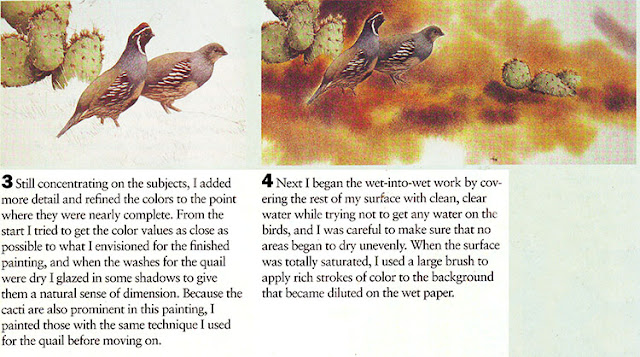

Now the fun really begins. I always paint the main subject first, wherever it may be, using a few controlled washes to establish its overall color. In each of these washes I try to get as close as possible to the final values of the painting. After the washes have dried I enhance the detail a bit, and then give the subject some depth and indicate the source of light by glazing in shadows. Having done all this, the main subject should be nearly complete, although I may decide to add a bit more detail later on because this helps to contrast the subject With the looser background.

With the center of interest already developed and dry, I’m ready to start the rest of the painting, and my favorite environments are painted Wet-into-Wet. This method allows for a great sense of spontaneity-those fortunate accidents in Which the painting seems to have a mind of its own- plus it keeps me from painting too much detail in areas that aren’t the center of interest. I start this process by carefully painting clean, clear Water right up to the edges of the subject, making sure that as little Water as possible runs into it. It’s very important, however that none of this halo of Water dries.

I’ll go ahead and use a large brush to soak the remainder of the surface-which is often the majority of it, given the odd sizes I’m Working with-and I’ll repeat this three or four times to be certain that the paper is totally saturated. I constantly Watch to make sure no areas are drying unevenly.

The paint I use is mostly pigment, and in the Wet-into-Wet areas the saturated surface will dilute this rich paint as soon as it’s applied. I use large brushstrokes for my color, with directional brushstrokes to guide the viewer through the painting. As the paint runs together with the Water my wet-into-Wet Wash is created, and now I can go to Work on textures. Salt applied to the Wash creates fantastic organic textures for foliage.

A palette knife-one of my favorite tools-can be used like a squeegee to create rocks or with only its tip or its edge to add or remove damp pigment, which is great for branches or weeds. I also like to add some opaque paint (sparingly) by spattering the foreground or highlighting the subject, and to create this paint I either add gouache or opaque white to my transparent colors. I recommend being very careful when adding opaque white, however, because the colors can easily become chalky and pale. A few flicks of the wrist on scrap paper should give you a good idea of how heavily your brush is loaded.

Sizing Up Your Work

Now the painting is almost complete, but before finishing I like to stand back and take a hard, objective look at it. With unusual formats like these, you need to be sure you have the right balance between the center of interest and the rest of the painting. Even though your subject may be at the edge of the painting you don’t want it to disappear, yet you also don’t Want it to be so visually dominant that the majority of the painting holds no interest. If the subject needs more detail in relation to the surroundings, this is the time to add it. Adding glazes of color can lighten or darken areas if needed, and it can soften the intensity of textures that appear too strong. But, despite these corrections, I try never to overwork a painting.

I just try to reach the point Where I’ve done all the improvements I can Without spoiling my intended effect. Remember, not all paintings need an unusual format. But the paintings that do-and these are the images I search for as a Wildlife artist-are the pieces that Will become more dynamic or exciting Within a new set of borders. So take a look at the subjects you’ve become comfortable with and see if they might benefit from a change of layout. Crop into them or zoom out into their environment to try to find new compositions. Then, as you start your next painting, don’t forget that a little change in the size of your pictures can lead to a lot of success.

Joe Garcia received his formal training from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California.

He now lives and works in julian, California, and is a member of the Society of Animal Artists.

Garcias work appears in numerous private and corporate collections across the United States and Canada, and he has more than 130 limited-edition prints available.

To see more of this work, visit his Web site at www.joegarcia.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

"Thank you for reading my blog, please leave a comment"